Around 252 million years ago, life on Earth came terrifyingly close to annihilation. The Permian–Triassic Mass Extinction (PTME), often called The Great Dying, wiped out up to 90% of marine animal species. Coral reefs collapsed. Complex food webs unravelled. Entire ecosystems that had flourished for millions of years disappeared.

But extinction is only half the story.

A new invited Perspectives article in npj Biodiversity explores what happened next: How did marine life bounce back after the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history? And perhaps more provocatively — was it really a “recovery,” or something more transformative?

The Biggest of the Big 5

The trigger for the PTME is widely linked to the eruption of the Siberian Traps Large Igneous Province — a vast volcanic event that unleashed enormous quantities of greenhouse gases. The consequences were catastrophic:

- Extreme global warming

- Ocean anoxia (widespread oxygen depletion)

- Ocean acidification

- Ecosystem collapse across marine environments

Permian oceans, once dominated by complex and stable communities, gave way to biologically impoverished Early Triassic seas.

For decades, scientists assumed that recovery from this devastation was slow and stepwise — a gradual rebuilding from the bottom of the food web upward. According to this model:

- Primary producers recovered first

- Herbivores followed

- Predators and apex predators returned last

- Ecosystem complexity was fully restored by the Middle Triassic

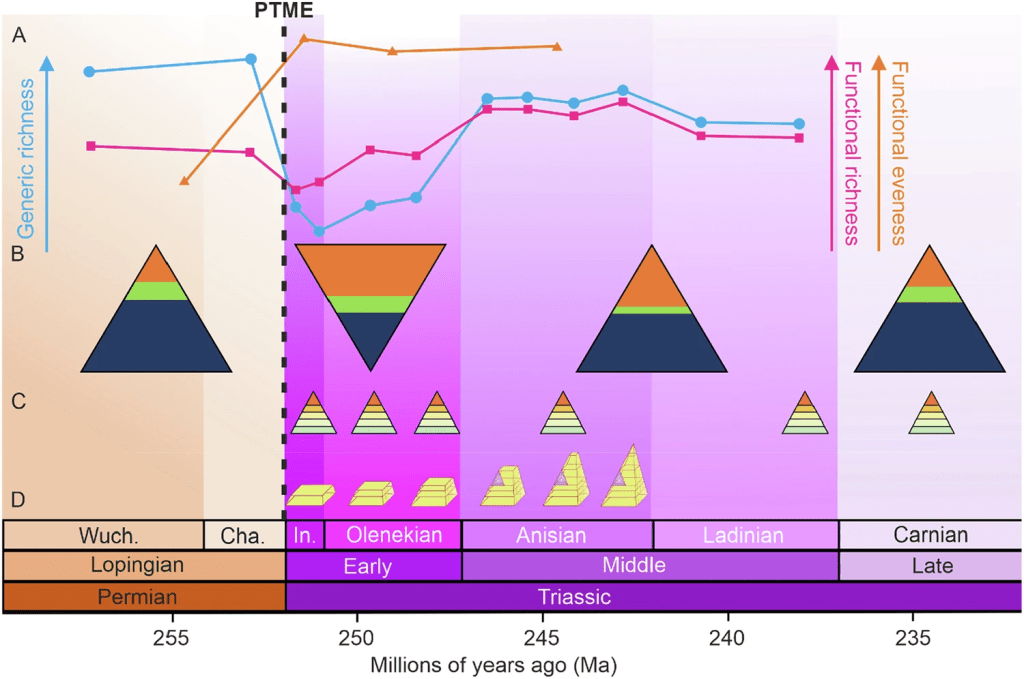

A. Changes in biodiversity and ecosystem complexity over time. The blue line shows how the total number of species changed, while the pink and orange lines track how diverse and balanced ecological roles were.

B. Ecological “pyramids” illustrating the diversity of major marine life groups from the Late Permian to the Late Triassic. Dark blue = stationary seafloor animals; Green = mobile seafloor animals; Orange = open-ocean swimmers

C. Fossil sites (Lagerstätten) from the Early–Late Triassic that preserve exceptionally detailed communities, revealing surprisingly complex food webs soon after the extinction.

D. A conceptual model showing the traditional idea of gradual, step-by-step rebuilding of marine food webs from the Early to Middle Triassic.

But is that really what happened?

Fast Rebound — or Fragile Reinvention?

Global fossil data tell a more complicated story.

Evidence suggests that multiple trophic levels — including high-level predators — reappeared relatively quickly after the extinction. Instead of a simple, bottom-up rebuilding process, Early Triassic ecosystems may have been “top-heavy” and unstable.

In other words, predators came back before ecological foundations were fully stabilized.

This challenges traditional recovery models and raises a crucial question:

Were ecosystems truly returning to their pre-extinction state — or were they reorganizing into something fundamentally different?

The new Perspective argues that we need to rethink what we mean by recovery.

Recovery vs. Restructuring

Does recovery mean:

- The return of lost species?

- The restoration of ecosystem structure?

- The reestablishment of ecological function?

- Or the rebuilding of complexity — even if composed of entirely new organisms?

The Permian world was dominated by distinctly Palaeozoic faunas. The Triassic ushered in the foundations of modern-style marine ecosystems. From this angle, the PTME may not represent a pause before restoration — but a reset that reshaped life’s trajectory.

Rather than a simple return to the past, the oceans may have undergone ecological restructuring, establishing new baselines more reflective of modern marine systems.

Blending Fossils with Ecological Theory

This Perspective connects to a recent NERC Exploring the Frontiers grant and integrates palaeontological data with community ecology models. By combining fossil evidence from multiple palaeolatitudes with ecological theory, researchers can test fundamental questions:

- How quickly did complexity return?

- Were food webs stable?

- Did biodiversity and function recover in sync?

- Can we distinguish between resilience and reinvention?

As fossil databases grow more comprehensive and analytical tools improve, deep-time ecology is becoming increasingly quantitative. We are moving beyond counting species to reconstructing entire networks of interaction.

Early-Career Leadership in Deep-Time Ecology

Led by PhD researcher Annabel Nicholls and supported by former project research assistant colleagues, the team includes Paul Wignall, Haijun Song, Jack Shaw, Andrew Beckerman, and collaborators. The work showcases how early-career researchers are driving forward new approaches to understanding biodiversity crises across geological time.

Why This Matters Today

We are living through a period many describe as the Sixth Mass Extinction. Ocean warming, deoxygenation, and acidification are not just ancient phenomena — they are modern realities.

The PTME provides a natural experiment on an unparalleled scale. It shows us:

- How ecosystems respond to extreme environmental stress

- That recovery may not mean restoration

- That ecological systems can reorganise into entirely new states

Understanding whether past ecosystems recovered or restructured changes how we think about the future of our own oceans.

If history teaches us anything, it’s this: life is resilient — but it does not necessarily rebuild what was lost. It adapts, reorganises, and sometimes reinvents itself.

And that distinction matters.

If you’re fascinated by palaeobiology, biodiversity, or the deep history of life on Earth, this open-access Perspective in npj Biodiversity offers a fresh and thought-provoking look at how life rebounds after catastrophe — and what that means for our planet today.

Read the article for free here: https://www.nature.com/articles/s44185-025-00117-2